Early involvement of structural engineers can be a game-changer for building projects. In the U.S. construction industry, many projects still follow a traditional design-bid-build sequence where structural experts are brought in only after an architectural concept is mostly complete. However, this conventional approach often leads to late-stage surprises, design revisions, and budget overruns. By contrast, engaging structural engineers from concept to calculation – i.e. from the earliest design ideas through detailed structural analysis – can dramatically improve constructability, accelerate schedules, and reduce costs. This article explores why early structural input is so valuable, dispels common misconceptions about when to involve engineers, and shares real U.S.-based case studies quantifying the benefits of early collaboration.

The Value of Early Structural Involvement in Design

Involving structural engineers at the outset of a project injects practical know-how into the creative design process. Structural engineers can quickly flag feasibility issues or efficiency opportunities that might not be obvious during conceptual architectural design. For example, they help identify structural spans, support layouts, and framing concepts that fit the project’s needs before the design progresses too far. It is much easier (and cheaper) to adjust a bay spacing or add a brace in the early schematic phase than to retrofit the building later when drawings are complete. One industry analysis noted that structural engineers and other designers have enormous power to set the stage for productivity improvement by improving the constructability of the design. In essence, early structural input ensures the initial concept is grounded in reality, preventing the classic scenario of an “architectural dream vs. engineer’s nightmare” down the line.

Crucially, early structural involvement fosters a collaborative design mindset. Engineers work alongside architects and developers to brainstorm design options and alternatives, not just validate a single idea. This often leads to creative solutions that neither party would have arrived at alone. Believe it or not, a structural engineer may suggest an innovative material or system that the architect hadn’t considered, expanding the design possibilities. By weighing different structural schemes (steel vs. concrete, moment frames vs. shear walls, etc.) along with their cost implications, the team can select the most efficient option before the project is locked into a less optimal path. As one engineer puts it, “with design options comes the idea of cost and value” – the sooner the owner and design team can evaluate these options, “the better”. In other words, early collaboration is a form of upfront value engineering that yields a more cost-effective design from Day One, rather than redesigning later to cut costs.

Improved Constructability and Fewer Design Revisions

One of the biggest benefits of involving structural engineers early is improved constructability of the design. Constructability means integrating construction knowledge into planning and design to optimize cost and schedule. In practice, this might entail aligning the structural grid with standard material sizes, planning for efficient slab pours, or ensuring there is space for connections and mechanical ducts. These considerations, when addressed at concept stage, make the eventual construction smoother and faster. According to Structure Magazine, integrating such construction know-how from the early design phase directly leads to optimized project cost and schedule, maximizing value to the owner. By contrast, a traditional sequential process (architect → then engineer → then contractor) often misses this integration. The result in those cases is numerous changes and constructability problems cropping up later. In fact, adversarial change orders are more or less built in to the conventional design-bid-build model, reducing a project’s value over its duration. Early structural involvement, especially under collaborative delivery models, breaks this cycle by catching issues before they become change orders.

Coordinating the structural design early with other disciplines also means fewer design iterations and revisions overall. When architects, structural engineers, MEP engineers, and contractors collaborate from the start, they can identify potential clashes or conflicts in the design early on, avoiding the costly and time-consuming revisions that would otherwise occur during construction. For example, an integrated design team might spot that an electrical shaft needs to pass through a beam bay – a conflict that, if caught in late design or in the field, could trigger significant rework. Research backs this up: if flaws or impractical elements in the design are not found in time, the downstream effects are often worse than expected, leading to delays and extra costs. Many design changes in construction are ultimately traced to things like impractical spans or support conditions that could have been addressed earlier. By involving structural engineers early, such problems can be designed out before they necessitate a painful redesign or a field fix.

The reduction in design revisions also translates to a leaner, more efficient permitting process. In the U.S., obtaining a building permit requires a complete set of coordinated construction documents, including structural plans and calculations. Projects that delay engaging structural engineers may find themselves scrambling to produce the structural drawings for permit, or worse – submitting incomplete plans that trigger multiple rounds of plan check comments. Early structural input ensures that by the time plans are submitted to the city, the architecture and structure are already in harmony. This results in fewer correction cycles with building officials and a faster path to permit approval. While quantitative data on permitting speed can vary, it stands to reason that a well-coordinated design will face fewer holdups. In collaborative projects, it’s common that structural engineering documents are ready on or ahead of the overall schedule, enabling parallel progress. Conversely, in a siloed process, late-arriving structural changes can delay permit approval and even construction start. Simply put, catching and resolving issues in the design phase – rather than during plan review or construction – saves weeks or months on the project timeline. This accelerated schedule can be crucial for developers aiming to get to market sooner.

Cost Savings and Value: Early Input Pays Off

From a business perspective, involving structural engineers early is an investment that yields measurable cost savings. The most obvious savings come from avoiding expensive redesigns and change orders. Changes made on paper in the early design phases are vastly cheaper than changes made in the field after construction has begun. Industry wisdom often cites that a change during construction can cost 10x more than if it were made during design – a reflection of rework labor, wasted materials, and schedule impact. By front-loading the design effort with structural input, owners can sidestep many of these later costs. For instance, rather than discovering that a planned open floor layout needs additional columns after bids (resulting in a costly addendum or change order), the issue would have been solved upfront at minimal cost. Projects with early engineering involvement tend to see fewer contingency drawdowns because fewer surprises emerge during build. As Structure Magazine observes, the traditional low-bid approach may offer a low initial price, but it “rarely [delivers] the lowest final cost” once all the change orders are tallied. Early collaboration, by contrast, aims to deliver the lowest final cost by preventing those change orders in the first place.

Moreover, early structural input can lead to direct cost optimizations in the design itself. Structural engineers can often propose more efficient structural systems or material choices that meet the project’s performance requirements at lower cost. This might include refining column spacing to shorten beam spans (reducing steel tonnage), selecting a lighter foundation system if soil conditions allow, or using innovative materials (like high-strength steel or engineered timber) where they add value. In one case, a structural engineer’s early suggestion to use a few short reinforced wall segments in key locations allowed a building to eliminate steel moment frames entirely, maintaining safety while significantly cutting material costs. The architect incorporated this idea during schematic design, and the change saved the owner the expense of those large steel frames. This kind of savings can easily be on the order of tens of thousands of dollars for a mid-sized building, not to mention the additional savings from a simpler installation process. The engineer’s involvement not only saved money but also time and headaches for the design team, who did not have to revisit the design later to retrofit steel bracing. Such proactive input early on can also help keep the project within the owner’s budget, reducing the need for a painful “value engineering” phase late in design (where features are cut to reduce cost). Instead, value engineering is essentially done continuously and constructively during initial design development.

There is also an opportunity cost angle to consider. When projects are delivered faster and with fewer problems, owners begin generating revenue sooner (for a commercial development) or users get to occupy the building earlier. General contractors benefit from smoother projects with less downtime, enabling them to finish on or ahead of schedule and move on to the next job. All stakeholders share in the reduced risk profile of a project where the structural design has been vetted from the start. While it’s hard to put a precise number on the ROI of early structural involvement across all projects, real-world projects have reported substantial gains. For example, many design-build projects – which by definition involve early collaboration between architects and engineers – have been delivered months faster than comparable design-bid-build projects, and often with lower total cost growth. The collaborative approach inherently drives efficiency. Owners who embrace early structural input frequently cite smoother bidding (since contractors see a well-thought-out structure in the plans), fewer Requests for Information (RFIs) during construction, and overall more predictable outcomes. All of these benefits ultimately translate to dollars saved.

Real-World Case Studies of Early Structural Collaboration

Case Study 1: Eliminating Costly Rework on a Commercial Build. In a recent U.S. project for a mid-sized commercial building, the architect’s preliminary design called for large steel frames to resist lateral loads (wind and earthquake). Bringing a structural engineer into a schematic design charrette revealed a smarter solution. The engineer recommended introducing a few short shear wall segments strategically in the floor plan, which provided the needed lateral strength without structural steel frames. The architect and owner were on board with this adjustment, and it was implemented early in design. As a result, the final design had no steel moment frames, simplifying the structure. The cost savings were significant – the expensive steel components and associated connections were no longer needed, saving the owner money on materials and labor. Just as importantly, the change streamlined the path to permitting. The structural engineer had verified the lateral system early, so there were no surprises during engineering plan review. The project sailed through the permitting process with minimal comments. In the end, the early collaboration in this case study not only saved an estimated 5-10% of structural costs but also avoided an extensive redesign that might have added several weeks to the schedule. The architect later noted that this early structural charrette “saved [us] time and headache as well” by heading off a problem before it ever occurred.

Case Study 2: Integrated Delivery for a Faster Timeline. A large healthcare facility project in California adopted an integrated project delivery (IPD) approach, embedding structural engineers in the design team from day one. Traditionally, on a complex hospital, the structural design might lag the architectural plan by months, with major revisions during coordination. In this IPD project, however, the structure and architecture were developed in tandem. This early integration led to remarkably few RFIs during construction (far fewer than industry averages for similar hospitals). It also meant that when the project hit the permitting stage, the drawings were fully coordinated – the first round of permits was approved with minimal corrections, and construction commenced earlier than on a comparable project that followed the usual process. The outcome was a measurably faster delivery: the hospital was completed several months ahead of a typical schedule. While many factors contributed, the owners credited early structural and contractor involvement as a key factor for the speed. This echoes findings by industry groups that collaborative design-build or IPD projects can be delivered significantly faster than design-bid-build ones, in part by overlapping design and construction and avoiding late-stage changes. The cost impact was equally impressive – the project finished under budget, as contingency funds for structural changes went largely unused. This case illustrates how early structural engineering input, combined with a team-oriented contract, yields tangible schedule and cost benefits in U.S. construction practice.

Case Study 3: Avoiding Change Orders in an Office Development. A developer in Texas undertook a multi-story office building with a tight budget and timeline. Initially, the project followed a conventional path where the architect worked out the concept drawings independently. Before finalizing the schematic design, however, the developer brought in a structural engineering firm (such as Aquinas Engineering) for a peer review and collaboration session. That early session proved invaluable – the structural engineers discovered that the architect’s sleek cantilevered facade concept would require expensive transfer girders and moment connections if left unaltered. They worked with the architect to subtly tweak column locations and added a few hidden braces into the facade design. These changes preserved the architectural vision but made the structural system far more straightforward to build. The payoff came later: when the contractor priced the job, the structural system came in well under the original budget estimate, and there were zero structural change orders throughout construction. A conventional approach likely would have led to redesigning the cantilever during construction (a much costlier moment to do so). By engaging the structural team early, the developer reduced structural steel quantities by roughly 8% (a substantial material cost savings) and kept the project on track for on-time delivery. This case reinforced to the owner and all parties that early structural input isn’t an added expense – it’s a prudent measure that preempts costly problems. As one industry publication notes, proactive problem-solving in a design-assist model increases value over a project’s duration, whereas an adversarial late change-order approach only decreases value. Here, early collaboration clearly increased value.

These case studies, while varied in building type and delivery method, all underscore a common theme: engaging structural engineers early leads to concrete time and cost savings. Whether it’s a modest commercial building or a large institutional project, the early involvement strategy pays off in fewer surprises and more efficient execution.

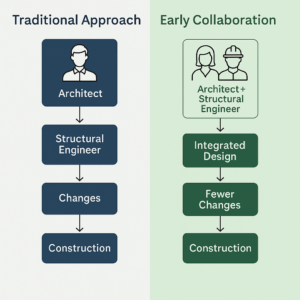

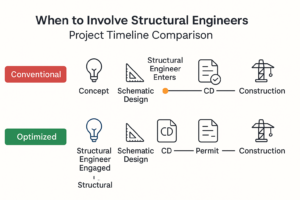

Conventional vs. Early Collaboration: A Process Flow Comparison

It’s helpful to visualize how the project delivery process differs between the traditional model and an early-collaboration model. Below is a simplified process flow highlighting key steps in each approach:

Conventional Project Delivery (Sequential Design-Bid-Build)

- Architect Develops Concept in Isolation: The architect creates the building concept and schematic design largely on their own, with minimal input from structural engineers or contractors. The focus is on aesthetics and space usage, with assumptions about structure.

- Structural Engineer Brought in Post-Concept: Once the architectural design is fairly developed, a structural engineer is engaged to “make it work.” At this stage, the engineer may find that some proposed design elements are structurally problematic or inefficient (e.g. long unbraced spans, insufficient room for structural depth).

- Iterative Design Revisions: The architect and structural engineer go back-and-forth adjusting the design. Changes like adding columns, beefing up structural members, or altering layouts might be required. This iterative revision could have been largely avoided with earlier coordination, but in the conventional model it happens mid-stream, sometimes causing the architect to revise their vision.

- Delayed Detailed Design Completion: Because of the late start on structural design, the overall construction document phase can take longer. The structural drawings might lag behind, and any major structural changes ripple into architectural, mechanical, and other drawings, prompting further revisions.

- Permitting and Bidding Phase: The completed plans are submitted for permit. Given the piecemeal coordination, plan checkers may issue comments that require revisions, leading to resubmittals. Bidding contractors might also submit many RFIs seeking clarity on conflicts or impractical details. In many cases, change orders are almost inevitable once construction begins, as uncoordinated issues come to light in the field. These changes often increase the cost and can extend the schedule as fixes are implemented.

- Construction Execution: The project proceeds, but unforeseen structural issues (like a needed beam penetration or a field-fit conflict between structure and HVAC) may cause work stoppages or redesign on the fly. The lack of early structural input manifests as reactive problem-solving during construction, which is the costliest time to do so. The end result is often a project delivered later than planned and over the original budget.

Early Collaborative Project Delivery (Integrated Design Approach)

- Conceptual Kickoff with Architect and Structural Engineer: From the very beginning (concept and schematic design), the architect and structural engineer sit at the same table. Together, they review the owner’s goals and the architectural vision, and the engineer provides immediate feedback on feasibility. For example, during concept sketches, the engineer might advise on an efficient column grid or flag a cantilever that would be costly – allowing the team to adjust the concept in real-time.

- Multidisciplinary Design Charrettes: The project team (which can also include mechanical engineers and even a contractor or cost estimator) holds collaborative design sessions. In these meetings, design options are explored with structural implications in mind. The structural engineer can propose alternatives (e.g. “What if we use a steel braced frame here instead of moment frame?”) along with rough calculations or rules-of-thumb to guide decisions. The team converges on solutions that balance aesthetics, cost, and performance.

- Concurrent Development of Architecture and Structure: As the design progresses into detailed stages, the architectural and structural plans evolve in parallel. Because the engineer was involved early, major structural decisions (materials, system layout, core placement, etc.) are already made and aligned with the architecture. The structural engineer produces calculations and drawings in step with the architect. Any minor conflicts that arise are resolved on the fly through close communication, rather than formal RFIs.

- Continuous Constructability Input: Throughout design, the structural engineer (and often the contractor or construction manager) provides constructability feedback. For instance, they ensure that connections have access for bolting/welding and that the design remains buildable with standard practices. This proactive problem solving in design adds value and prevents issues that would decrease value later. By the time construction documents are ready, the plans are coordinated and straightforward to build.

- Streamlined Permitting and Bidding: The permit submission from an integrated team is typically more complete and internally consistent. Code requirements (like structural safety factors, lateral force resisting system details, etc.) have been vetted from early on. Thus, permitting authorities are less likely to find major issues, and approvals come faster. When the project is bid out, contractors can clearly understand the design intent; they encounter fewer ambiguities and submit fewer RFIs. Early collaboration may also allow fast-tracking parts of construction – for example, starting foundation work while upper floors are still being designed – because the engineer has been involved in phasing discussions.

- Construction with Fewer Surprises: Once construction starts, the benefits of early structural input become fully apparent. The structure goes up as planned with minimal changes. The construction team isn’t forced to solve last-minute structural problems because those were already ironed out in design. Fewer change orders occur, and the project stays on schedule. In many cases, the collaborative approach results in completion ahead of schedule, as there were no major delays from design errors or late fixes. All parties – architect, engineers, contractor, and owner – benefit from a smoother process that was set in motion by early teamwork.

In summary, the conventional model tends to be reactive, addressing problems after they occur, whereas the early collaboration model is proactive, preventing problems before they happen. The process flow with early structural involvement builds in quality and efficiency from the start, leading to a more predictable and successful project delivery.

Debunking Common Misconceptions

Despite the clear advantages, some misconceptions persist about involving structural engineers early. One common myth is: “We don’t need a structural engineer until after the architectural design is mostly done.” In reality, waiting that long virtually guarantees some level of redesign. Structural requirements (columns, lateral bracing, floor thicknesses, etc.) will inevitably force changes to an unvetted architectural design. It’s far better to have engineers contribute during concept development to ensure the design is feasible from the start. This doesn’t mean the engineer will override the architect – rather, they will act as a partner to make the architect’s vision viable. Early input can enhance creativity by offering solutions (like new materials or structural systems) that enable ambitious designs, as opposed to limiting the design.

Another misconception is that involving engineers early will inflate upfront design costs and take too much time. It’s true that having additional design meetings or charrettes early on requires a small investment, but this pays for itself many times over by preventing expensive problems later. As one structural engineer noted, you might even get an initial concept consultation as a free service, but “it is worth it… even if you have to pay a few hours of your engineer’s time.”. Those few hours can reveal ideas to make the project more cost-efficient and save far more hours (and dollars) in avoidable revisions. Early collaboration shouldn’t be seen as an added hassle, but as a smart way to de-risk the project. Industry practice is shifting in this direction: more owners are realizing that spending, say, 1% more on design (to involve all key players early) can chop 10% or more off the construction cost through greater efficiency.

There’s also sometimes a fear that bringing engineers (or contractors) in early will dilute the architect’s control or lead to design compromises. The truth is, when done right, early collaboration preserves and strengthens the design intent. The architect retains creative leadership, now bolstered by real-time feedback. Engineers are not there to say “no” to design ideas; they are there to turn ideas into reality and often find a “yes, and…” solution that satisfies aesthetic, structural, and budget goals. The end result is usually a design that the architect and owner are happier with, because it stands a better chance of being built as imagined, on time and within budget. In short, early structural involvement is not a threat to design quality – it’s a means to achieve design excellence without unpleasant economic surprises later on.

Conclusion: Build a Strong Foundation Through Early Collaboration

In the fast-paced and high-stakes world of U.S. construction, every week and every dollar counts. Involving structural engineers early in the project lifecycle is a proven strategy to save both time and money while enhancing the overall project outcome. From improved constructability and fewer change orders to accelerated permitting and optimized costs, the benefits of early structural input are clear and well-supported by industry experience. The traditional approach of isolating disciplines until late in the process is giving way to a more integrated model – one where architects, structural engineers, and other professionals co-create solutions from the concept to calculation stage. This collaborative ethos results in designs that are innovative yet practical, ambitious yet achievable.

For architects, developers, and general contractors, the message is clear: engage your structural engineering partners as early as possible. Doing so will reduce guesswork, minimize rework, and unlock cost-effective solutions that might otherwise remain undiscovered. Instead of viewing structural input as a mere box to check for compliance, treat it as a source of value and creativity that can propel your project forward.

As you plan your next project, consider reaching out to a structural engineering firm early in the conceptual phase. Bring them to the table for that initial idea session or feasibility study – you’ll likely be amazed at the insights they can provide. Remember that a strong design is built on a strong foundation of collaboration. By integrating the “brains” of engineering with the “vision” of architecture from the start, you set your project up for success on multiple fronts.

Call to Action: Don’t wait until designs are set in stone to involve the experts who literally design the stone (and steel and concrete). Whether you are an architect refining a bold concept or a developer budgeting your next venture, involve a structural engineer early to save time, save money, and build smarter. At Aquinas Engineering, we specialize in early-stage structural consulting to help bring concepts to life efficiently and safely. Reach out to our team to explore how early structural input can streamline your project – from concept to calculation, we’ll help you deliver a better building. Embrace early collaboration, and watch your project soar to new heights on a solid structural foundation.

By Aquinas Engineering